Sometimes, the story behind an album is excellent enough that we need not compile a collection of several records. Instead, today, we are enjoying just one album, the exceptional Jingul by Ustad Noor Bakhsh. This is the story of how a 76-year-old master released his debut effort, triggering his first world tour and certain global acclaim after a lifetime of perfecting his art.

Balochistan is a vast historic region of South Asia. Spread over three countries, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, where it constitutes the country’s largest province making up nearly 44% of its total area. It is however by far its most sparsely populated, with only 43 people per square km; for reference, London holds nearly 15,600 people per square km. Despite being relatively inhospitable to humans, the province of Balochistan is an area of incredible natural beauty, boasting mountains, desert, forest, and a huge 800km of coastline. The region is home to 590 recorded species of animal, including two endemic rodents, the Balochistan forest dormouse, and Baluchistan pygmy jerboa.

Born and bred in the region, Ustad Noor Bakhsh lives and breathes Balochistan. Originally from a nomadic family of goat herds, he left the family trade to take up music at the young age of 12.

The honorific ‘ustad’ roughly means ‘master’ and is only ever bestowed upon the very cream of the most deserving. The most revered artists, the most exalted teachers, the creatives perched at the unassailed peak of their chosen field. Our musician du jour easily meets the brief. At 12, he became a student of the benju master Ustad Khuda Bakhsh (no relation), who had him playing weddings within a couple of years. At 15, he became vocalist Sabzal Sami’s live accompanist, and would remain with the singer for thirty subsequent years.

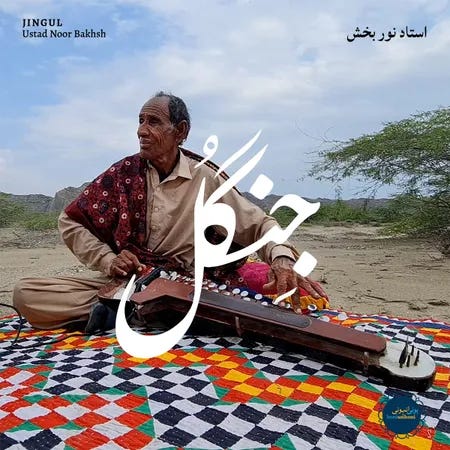

By 2022, Ustad Noor Bakhsh had been playing his electric benju to great local acclaim for well over half a century at weddings and other celebratory events both as a soloist, and accompanying other musicians. Despite his local fame and adoration, he remained largely unknown to the rest of the world, but that was soon to change!

For anyone frantically googling “what on earth is a benju?!”, don’t worry, this is the bit where I indulge my musical instrument nerdery: The benju is a sort of zither, loosely related to a dulcimer, with the addition of a keyboard. Roughly a meter long and 10cm wide, it’s fitted with six strings, four of which provide the bordun, or drone; the other two of which are tuned in unison and fretted meaning they can be shortened using the keyboard. The strings are plucked rather than struck.

The benju is thought to have been adapted from the taishōgoto, a popular instrument in Japan whence it travelled to Balochistan with Japanese traders in the 1920s. It’s been reported that the version of the instrument first introduced to the region was in fact a child’s toy. Over the years, it was adapted by local craftsmen to become a key instrument in the traditional music of the area, in particular Western Pakistan. The version Bakhsh plays is an adapted electric benju which he’s hooked up to a car battery and an amp.

In 2018, Daniyal Ahmed, an anthropology professor at Karachi’s Habib University, chanced upon a video of Bakhsh that was circulating on social media. Ahmed had long been dedicated to amplifying the traditional music of rural Pakistan, occasioning the odd release via his independent imprint Honiunhoni. The spell this video cast over him was strong; he simply had to go find the master.

As Ahmed started making plans for his journey, a global coronavirus pandemic shut down the world, so he had to indefinitely postpone his expedition. This only intensified the itch. By 2022, when he was finally able to make the trip, he was more determined than ever. He travelled the six hours from Karachi to Pasni (the fishing port named in the description of the video he’d seen) and proceeded to just ask around for Bakhsh.

As a local legend, people were very familiar with the benju-wala, but nobody knew precisely where he might be found. Undeterred, Ahmed drove around the nearby villages for a while continuing to quiz locals until – on a deserted road in the middle of nowhere – he encountered a man sat beside a broken-down motorbike, he naturally stopped to offer help. As he got out of his car, he couldn’t believe his eyes, the man by the bike was Bakhsh!

Ahmed explained his mission, and Bakhsh invited him back to his place for a few days. Once there, they arranged to record a few tunes for posterity.

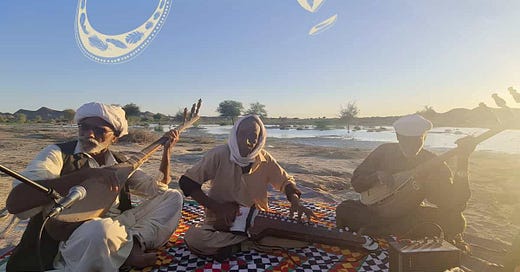

Bakhsh set himself up on a colourful quilt on the Shadi Kaur dam near his village. He was joined on his quilt by two friends, Doshambay Sabir and Jamadar Guahram, both playing damboora (a long-necked fretless lute). As the sun set on another warm Balochi day, the three chums proceeded to record a handful of traditional tunes as well as a Bakhsh original composition which would give its name to the album Ahmed later produced with the recordings: Jingul.

The word ‘jingul’ translates from Balochi as ‘lark’. The song is named for the small bird that frequently visits Bakhsh in his yard whose song inspired the melody. The jingul’s feathers have even made their way into the Balochi script on the cover of the vinyl release – designed by artist Abeera Kamran.

A truly stunning album; its beauty and poetry are carried by the effortless mastery and improvisational prowess afforded by sixty years of experience.

I’ve been ridiculously lucky to see the Ustad three time in concert. The first was at London’s Southbank Centre during Dialled In’s South Asian Sounds takeover in March 2024.

I was eagerly anticipating seeing the master on stage, although slight trepidations around the choice of venue persisted. Having attended a fair few gigs by a diverse variety of artists in the various rooms at Southbank, I went in to this one expecting the usual crowd of dusty snobs sitting immobile for fear of offending anyone with the liberty of enjoyment. How wrong I was!

Barely 10 minutes into the show, two especially eager audience members ran down to the front of the stage to enjoy a dance only to be promptly ushered back by security to their allocated seats. Undeterred, as the opening chords of the next song rang out, they ran back to their impromptu dancefloor, this time joined by a handful of others; out jumped security again… and so continued the merry-go-round until security gave up and a large portion of the crowd spent the rest of the show dancing in front of the stage (your humble author amongst them!) A vibrant energy filled the usually cold space as it was turned from sterile English concert hall to a rowdy South Asian party, a celebration of life and music that left every soul in the room revitalised and enthused.

The second show was in one of the hundreds of tiny tents at Glastonbury festival, of course, an excellent show. The most recent performance took place in Dalston’s historic experimental arts venue Café Oto. This was by far and away the finest of the three shows. From beginning to end, the room was bouncing to the sweet melodies of the benju, interspersed by sporadic stories and poems delivered by Bakhsh in Urdu (to the great delight of the roughly two thirds of the audience forming the Pakistani contingent. The rest of us just smiled and laughed when everyone else did…)

For all three shows, Bakhsh was joined on stage by his recording colleague Doshambay Sabir. Sabir took up the damboora as a child but was forced to become a truck driver to earn a living. He never let his first love go however, and always kept the instrument in the back of his truck, playing at every opportunity. He has now accompanied Bakhsh on his world tour, playing every show alongside him.

Daniyal Ahmed also joined them, playing both damboora and flute. A keen flautist, Ahmed is new to the damboora. He explains “Doshamaby has taught many people to drive a truck, but he has only taught one person the damboora” Ahmed also served as MC and general hype man, spending as much time dancing in the crowd as on stage playing.

As with the album, the music at all three shows was absolutely flawless. The kind of flawless one can only achieve after multiple decades of daily practice. The kind of flawless that earns the purveyor a title like ‘Ustad’.